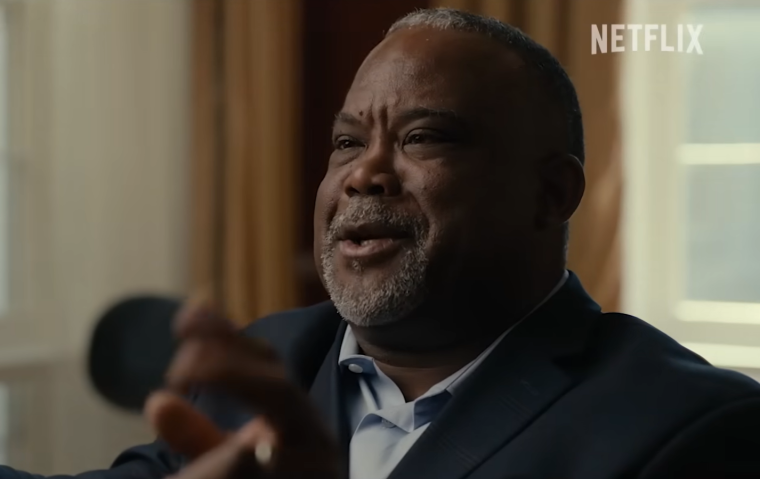

Michael Johnson, a former police detective in Plano, Texas, who served as the youth protection director at the Boy Scouts of America, says the embattled youth organization blocked his efforts to institute child protection measures due to fear of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Johnson made the claim in a new Netflix documentary released Wednesday called “Scouts Honor: The Secret Files of the Boy Scouts of America,” which recounts the Boy Scouts of America’s decadeslong cover-up of sexual abuse cases and chilling accounts from several now-adult men on the abuse they suffered as minors while they were a part of the organization.

“As the new youth protection director, as I was starting to wanting to do some what I thought were very medium-level policies and content training, upgrades for youth protection. I kept getting told [by a BSA executive] that the Mormons may not like that, the Mormons don’t like that,” Johnson recalled.

“I said, I came to work for the Boy Scouts of America. I came here to protect the kids, the boys and girls of the Boy Scouts of America. I am not working for the Mormon Church and the Catholic Church. And I remember, I’ll never forget this: Jim Terry, assistant chief scout executive, told me, ‘Mike, you need to understand something.’ I’m like, ‘What is that, sir?’ He says, ‘The Mormons are sacrosanct.'”

At the end of 2019, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints cut all ties with the BSA, noting that they were shifting toward a more globally focused youth leadership and development program, ending their 105-year relationship. About 20% of the BSA’s members were practicing Mormons at the time, and the youth organization lost some 400,000 troops from the LDS.

Neither the BSA nor the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints responded to requests for comment from The Christian Post Friday. But in an earlier statement to Axios, the youth organization said they were disappointed by Johnson’s comments.

“We cannot speak to the many instances of hearsay and personal opinions expressed by Michael Johnson. We are disappointed to hear Mr. Johnson’s characterization of the program he spearheaded and the concerns he raised, especially given his past public support for the robust measures the BSA instituted at his recommendation,” the BSA said.

The documentary comes just two weeks after the Boy Scouts of America began processing claims under a $2.4 billion bankruptcy plan for more than 80,000 victims who say they were abused while they were a part of the scouting program.

“Sexual abuse. Those two words are kind of PG. It’s easy to say. People are uncomfortable with sexual abuse; people don’t want to visualize that these young men and now men that are on this lawsuit, were having sex with men in their cars, in tents, at their house,” explained Johnson, who spent 16 years investigating crimes against children as part of the Plano Police Department in Texas before going to work for the BSA in 2010.

“I say these things, and I’m not trying to say them to incite you. But that’s what sexual abuse is. We’re talking about these men who have experienced or suffered X-rated activities as children in the scouting program, and who are they going to talk to about it? They’re still grappling with their own internal experiences, demons, some of them with what happened,” Johnson said.

Documents kept by the BSA for nearly a century, known as the “perversion files,” highlighted a “sordid history of child sexual abuse,” previously reported by CP. The narratives of the men featured in the Netflix documentary paint a compelling picture of the abuse.

One victim recalled how he was part of a scouting group whose leaders targeted single mothers and convinced them that their sons would be safe with them.

Instead of being good role models for the young boys, the scout leaders were accused of trafficking them to men from around the world who subjected them to repeated acts of rape and other abuse until police eventually broke up the ring.

Despite the thousands of abuse claims against the BSA, Steve McGowan, former general counsel for the BSA, framed the abuse as a societal problem, not an organizational one.

“I will tell you that we’re a microcosm of our entire society. If we had a problem, our society had a problem; many other institutions had the problem. We just happen to be the one with the deep pocket right now and the one that’s willing to make the social commitment to try to make it right and to try to apologize, to try to do everything we can to keep it safe, and try to compensate for these victims, but then continue the mission,” McGowan said. “And many of the survivors are very clear. They want scouting to continue because of the good it did. We want to continue to do that.”

Johnson insists that McGowan is being deceptive.

“The messaging he wants out there is that Boy Scouts is like any other organization in America and that these guys could come from anywhere, and there’s nothing we can do to prevent them. All of that is not true,” said the former detective.

“Boy Scouts is exceptional in the opportunities that it presents to perpetrators to access children and no to very low supervised situations. Name another youth-serving organization that has overnight access to kids over multiple days. Name another organization that a scoutmaster has the power over whether or not this youth can become an Eagle Scout,” he said.

“Now you back up a little bit, and you think to yourself, how easy is it to get into scouting? And so now you start to see where those weaknesses are. It’s removing those risk areas, known risk areas that helps you create this safer environment for kids who participate in scouting programs,” he added. “You talk to a lot of these young men; they’ll tell you, ‘My parents dropped me off at his house.’ We’ve had cases where the adult stayed the night at the kid’s house.”

Contact: leonardo.blair@christianpost.com Follow Leonardo Blair on Twitter: @leoblair Follow Leonardo Blair on Facebook: LeoBlairChristianPost

Free Religious Freedom Updates

Join thousands of others to get the FREEDOM POST newsletter for free, sent twice a week from The Christian Post.

![[Video] More – Aghogho » GospelHotspot](https://gospelhotspot.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/More-Aghogho.jpeg)