Today is the second of three installments of my interview with Brian McLaren. He asked me three questions about my book The Bible Tells Me So: Why Defending Scripture Has Made Us Unable to Read It

Today is the second of three installments of my interview with Brian McLaren. He asked me three questions about my book The Bible Tells Me So: Why Defending Scripture Has Made Us Unable to Read It and I in turn asked him three questions. We are posting the exact same post on each other’s blogs simultaneously; we figured the internet has enough room. Brian’s blog is here if you’d rather see what it looks like from his part of cyberspace.

As I’m sure many of you know, Brian’s latest book is We Make the Road by Walking: A Year-Long Quest for Spiritual Formation, Reorientation, and Activation—52+short chapters that give an overview of the biblical story and a fresh introduction or re-orientation to Christian faith.

Also, note the excessive wordiness of my answer compared to the crisp, succinct nature of Brian’s answer. Whatever.

Brian’s 2nd question:

I often say that for 500 years Protestants have been trying to prove to Catholics that a religion can exist with an infallible book rather than an infallible pope. But now the question remains – can a religion exist without an infallible book? How do you think Christians will answer the authority question 25 years from now – those, I mean, who are no longer appealing to an infallible pope or book?

I think that’s a good way of presenting part of the Protestant predicament. It’s certainly the case that biblical authority, however conceived in the early Protestant reaction to Roman Catholicism, has taken on a life of its own—a “paper pope,” as it were. I have knowledgeable friends who would call that a bit of a low blow, because the role of the Bible—including in Roman Catholicism—has always been central to faith and life. Still, particularly in America, I can’t help but think that what conservative Protestantism expects the Bible to do for them—an inerrant guide to all matters of faith and life–is not what the Bible is meant to do (which is one of the central themes of The Bible Tells Me So).

I know, Brian, that you’ve written about how the Bible functions uniquely in America as a “constitution”—authorities interpreting the sacred, binding text to define law for the rest of us, and which correlates to the rejection of monarchy by the colonists. I agree with this comparison and I have found it a helpful way of explaining how Protestant expectations of the Bible have a significant cultural dimension.

The Bible, however, is a problem—and I’m sure you agree. All Christians should want to engage knowledgably and humbly the Bible as we walk the path of Christian faith. But the problem that you’re touching on is one of faulty expectations about what the Bible can actually do.

Seeing the Bible as a source of binding information for all matters touching on our faith and accessible by exegesis runs into well known recurring problems—namely Christians rarely agree on a lot of things about how the Bible is to be understood and listened too, which bring us back to the “paper pope” or “constitution” metaphor. The Bible is too diverse to function that way. What sounds like a good idea in the abstract becomes a problem when you actually start going to the Bible to provide answers to all our questions.

In a word, you find that the Bible has to be interpreted. And if the history of Christians and Jewish interpretation of the Bible has shown us anything, it is that interpretation and the interpreter’s context can never be severed. We read Scripture from our own cultural vantage point, much of which is below the level of the surface of the conscious mind.

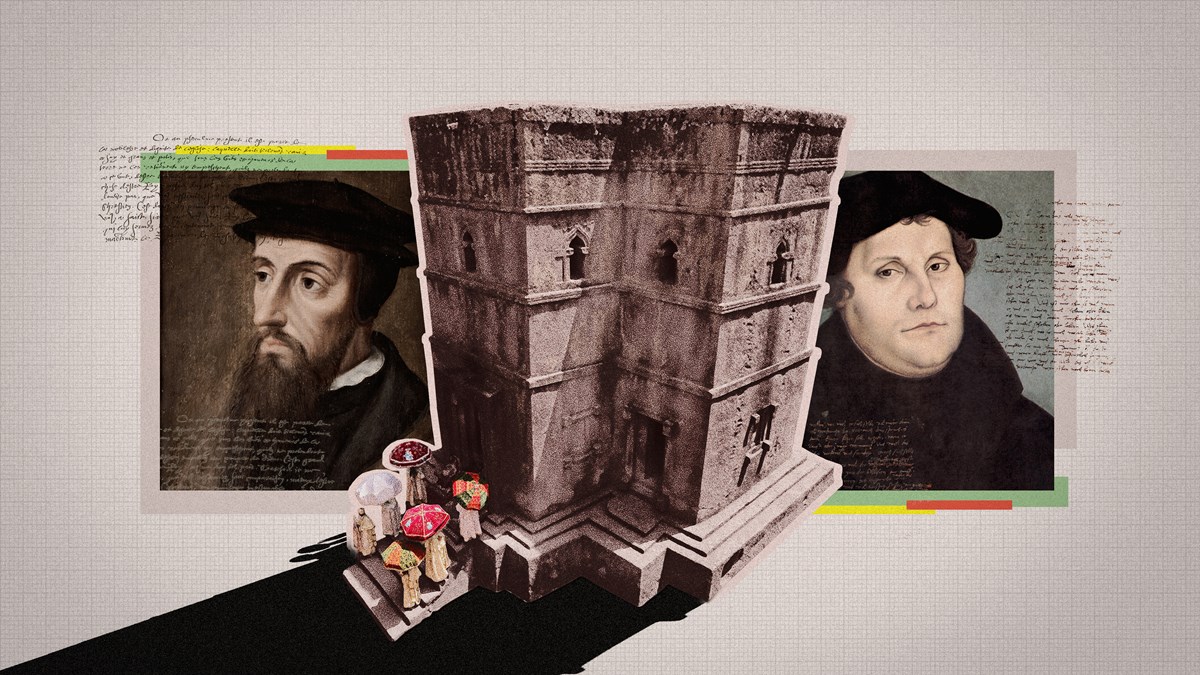

What happened in the wake of the Protestant Reformation, where Scripture’s plain and authoritative voice was called upon to settle all sorts of issues? Interpretive diversity. Do you baptize infants or adults? Do you sprinkle or immerse? What does it mean when Jesus says, “This is my body?” Is Jesus really “there” in the Eucharist? In what sense is Jesus “present” in the bread and wine?

There’s a reason thousands of Christian denominations and sub-denominations exist, especially in Protestantism: the Bible requires interpretation in order to be the final court of theological appeal. But the Bible itself is notoriously difficult to nail down on many matters. There’s enough flexibility there to allow for multiple legitimate interpretations. Related to this is the concept of “inerrancy.” It’s not a helpful term for guiding our use of the Bible. Functionally, what the Bible is inerrant about and how it is inerrant varies among Christians.

Anyway, despite all this, and now finally getting to your question, I’m not sure “can a religion exist without an infallible book?” is the best question to ask. I suppose religions can in general. Whether Christianity can is another question, and I suppose we’ll never be able to test the hypothesis, because the Bible is never going to leave the life of the church. The Christian faith is too biblically engaged and defined to contemplate a life without the Bible.

Scripture—in all its diversity, complexity, and messiness—presents the Christian story. It always has, it always will. It’s not going anywhere, and we shouldn’t wish it to. So the more pressing question, as I seed it, is: what kind of “Bible” is the church going to engage in faith and life in the coming decades, generations, etc.? A “paper pope” or constitution?” Or something else?

In other words, what expectations of the Bible will we have as we try to follow Jesus here and now. What is the Bible there for? How will that question be answered differently today and tomorrow than how it’s been answered over the last century or so in conservative contexts?

Again, I‘ve tried to make very clear in The Bible Tells Me So that the Bible isn’t the problem. The problems begin when we place our own expectations for the Bible onto the Bible and that the Bible simply can’t bear without a lot of fudging. In that respect, not only can but I think Christianity must learn to exist without an “infallible book” as it has been operating for at least western conservative Christians. The question needs to be asked more deliberately, “infallible for what?” That, I think, is a very important question to keep asking ourselves.

My brief answer to that question is that the Bible models for the faithful and humble our own diverse spiritual journey of faith in God and Christ, moving us toward greater love of God and love of others. “Knowing Scripture” is not the end goal. Knowing God in Christ is. The Bible doesn’t say “Look at me!” but “Look at me so you can look through me, past me, to God.” Rather than being the “center” of our faith, the Bible decenters itself and puts Christ in the center where he belongs.

Pete’s 2nd question:

When I was in graduate school, a question–actually, a two-part question–began to surface for me: “What is the Bible, really, and what do we do with it?” Realizing that I had never asked myself these questions before was a moment of profound self-awareness, but having my preconceptions challenged through a serious academic study of the Bible raised them and they have stuck with me ever since. So, I know this is totally unfair, but how would you answer a curious person who knows little to no Christianese and really wants to know what you think? What is your elevator pitch answer to those questions?

So I’d say the Bible is a library – a collection of literary artifacts. The first and larger part of it is from the Jewish people, spanning several centuries of their history. It includes poetry, a bit of philosophy, a fascinating genre called prophecy (which is something like ethical social commentary today), and a whole lot of storytelling.

The second part collects literature from the early years of a movement that arose within Judaism, centered in the life and teaching of Jesus. This collection begins with four gospels – another unique genre, not to be confused with simple biography or historical account. It is followed by a kind of gospel-appendix or sequel called Acts of the Apostles.

Then there are a series of epistles or formal letters that circulated among early centers of this movement. Finally there is an enigmatic text called Revelation or Apocalypse, which is an example of a genre called Jewish Apocalyptic literature.

Together these documents are tremendously important, because they help us reconstruct a vital conversation over many centuries about God and life. In that conversation, millions of people have found meaning and purpose for their lives; in fact, by entering that conversation, they have experienced an encounter and engagement with God.

![[Video] More – Aghogho » GospelHotspot](https://gospelhotspot.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/More-Aghogho.jpeg)