If Abraham Lincoln still matters to Americans in the 21st century—and he does—a major reason is that there’s much at stake politically in how we remember him. This is as true of Lincoln’s religious beliefs as for any other part of his life. In a nation deeply divided over the proper role of religion in the public square, it makes a difference whether our greatest president was a religious skeptic or an orthodox Christian, a devotee of Thomas Paine or a disciple of Jesus.

The debate began almost immediately upon his death. Although Lincoln had never joined a church, Christians typically insisted on his devout faith. Although the late president had quoted extensively from the Bible, non-Christians protested that he doubted much of what it said.

Professional historians joined the debate in the first half of the last century, but they haven’t resolved it. There are outliers, but most agree that by the time of his presidency, Lincoln was not an atheist, if he ever had been. Most agree, as well, that he was almost certainly not an orthodox Christian, if by that we mean someone able to assent wholly to one of the major Christian confessions. It’s been difficult to determine beyond this, thanks to limitations in the surviving evidence.

After his death, countless acquaintances claimed intimate knowledge of the state of Lincoln’s soul, but these testimonies are hopelessly contradictory and their objectivity is doubtful. In addition, Lincoln’s voluminous personal papers are characterized by a pervasive, seemingly intentional ambiguity. Lincoln scholars all acknowledge that he used biblical language, but the questions of why he alluded to the Bible and how much of it he believed remain unanswered—and are probably unanswerable.

Lincoln and Scripture

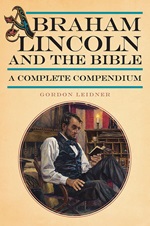

And yet we persist in asking these questions, as two major new studies of Lincoln’s religion attest. In Abraham Lincoln and the Bible, author Gordon Leidner explores how Lincoln appealed to Scripture, what he said about it, and how he may have been influenced by it. He wisely passes over the competing claims of Lincoln’s contemporaries and focuses on Lincoln’s own words, meticulously combing through the nine published volumes of Lincoln’s speeches and correspondence for clues.

Hoping that these will “speak for themselves,” Leidner concludes the biography with a 55-page appendix describing in detail 199 instances of Lincoln quoting or alluding to Scripture. From these, Leidner draws two conclusions: first, that Lincoln “fully accepted the moral authority of the Bible”; and second, that he drew effectively from it “to lead his followers to a higher moral plane.”

The first conclusion is possibly correct but hard to prove. Curiously, not once did Lincoln appeal to the Bible to make a moral argument against secession, even as a chorus of ministers across the North cited Paul’s instruction in Romans 13:1—“Let everyone be subject to the governing authorities”—to insist that disunion was an offense against God. When Lincoln did allude to Scripture in making a moral argument, it was almost always with slavery in mind.

And yet Lincoln emphasized the Declaration of Independence far more than the Bible in building his case against human bondage. He described the assertion that “all men are created equal” as his “ancient faith.” He argued pointedly that the immorality of slavery could be proved “without reference to revelation.” In sum, without penetrating Lincoln’s heart, it’s hard to know whether he viewed the Bible as morally authoritative, as Leidner claims, or selectively cited it when it corroborated what he already believed.

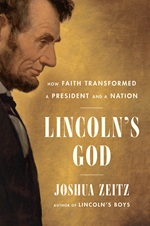

Image: Illustration by Mallory Rentsch / Source Images: WikiMedia Commons

Abraham Lincoln

Leidner’s second conclusion is correct, technically, but it’s also incomplete. There’s no doubt that Lincoln sometimes quoted the Bible to call Americans back to what he called “the better angels of our nature.” More than once, he challenged defenders of slavery by reciting the Golden Rule. Most famously, in his second inaugural address, delivered only weeks before his death, Lincoln quoted the Bible four times as he meditated on the possibility that God was judging both the North and South for the national sin of slavery.

But these instances were far from typical of how Lincoln appealed to the Bible. Many of the quotations that Leidner cites are trivial snippets, such as “four score” or “brought forth.” Others—like “two-edged sword,” “loaves and fishes,” and “daily bread”— appear in Scripture but were also common colloquialisms in Lincoln’s day. As Lincoln used them, they carried no moral connotations at all, and whether Lincoln (or his audience) believed in the moral authority of the Bible was irrelevant to how they functioned. Even the longer quotes Lincoln employed were frequently wrenched from their biblical contexts and added little substance to the points Lincoln was making.

A prime example of this is the best known of Lincoln’s biblical quotations: “A house divided against itself cannot stand.” This approximate quotation from an aphorism of Jesus (found with minor variations in Matthew, Mark, and Luke) became a staple in Lincoln’s famous 1858 debates with Democratic Senator Stephen Douglas. In its gospel context, Jesus was ridiculing the Pharisees’ claim that he cast out demons by the power of Satan. Lincoln was making a rather different point, namely that free-labor and slave-labor systems are fundamentally incompatible.

That same year, Senator William Seward, Lincoln’s main rival for the Republican presidential nomination in 1860, made essentially the same argument as Lincoln but spoke of an “irrepressible conflict” between two opposing systems instead of “a house divided.” The two phrases could have been used interchangeably, but Lincoln’s was rhetorically more effective. Unlike Seward, Lincoln had hit on a widely recognized and easily understood figure of speech to convey his main point. Although he was quoting Scripture, he was not, in this context, making a substantively biblical argument.

But he was signaling Christians in his audience that he had read the Bible. Cognitive psychologists call such signals “epistemological cues,” indicators that the speaker or writer is “one of us” and can be trusted. I’m not maintaining that Lincoln did this consciously, although at times he may have been. Much less am I implying that he sometimes did so cynically or disingenuously, although we can’t completely rule that out. But there is no denying that, by the end of his life, Lincoln had become a master at appealing to Christians in the electorate, and his deft use of biblical language was likely one reason for his success.

Appeals to evangelicals

This, at least, is one of the conclusions of Joshua Zeitz in his book Lincoln’s God: How Faith Transformed a President and a Nation. Zeitz, a Politico writer and author of other historical books, confidently describes Lincoln’s religious path as a “spiritual journey from skeptic to believer.” According to Zeitz, Lincoln was radically skeptical as a young adult, then became vaguely “religious” in his middle years, though he remained unpersuaded by Christian dogma and kept his distance from institutional Christianity.

During the Civil War, however, Lincoln “underwent a spiritual renewal,” a transformation likely accelerated by the death of his little boy, Willie. By the second half of his presidency, Zeitz argues, Lincoln believed strongly in God’s sovereignty over the affairs of nations, although he still stopped short of believing in a personal God, much less in Christ as savior. Lincoln’s God, Zeitz concludes, was “a distant and unknowable force, his will mostly indiscernible to men and women.”

With minor variations, this echoes the prevailing view among Lincoln scholars. The real value of Zeitz’s work is the provocative delineation of how Lincoln interacted with northern evangelicals during his presidency. As Zeitz demonstrates, they both shaped and were shaped by the Civil War.

Until the 1850s, most evangelical clergy focused on preaching the gospel and promoting personal piety, while keeping their distance from politics. The sectional crisis changed this. Deeply disturbed by southern politicians’ apparent effort to spread slavery across the continent, northern clergy increasingly concluded that political engagement was not only permissible but a sacred duty. With the firing of the first shots at Fort Sumter, evangelical leaders abandoned any lingering hesitation and publicly and wholeheartedly supported the war, defining it not merely as a necessary evil but as a God-ordained, holy crusade. In short order, northern evangelicals not only abandoned their previous understanding of the separation of church and state, but also effectively became an extension of the Republican Party. No segment of the electorate supported Abraham Lincoln more faithfully.

Lincoln was not oblivious to this. If Zeitz is correct, he did everything he could to promote it, in the process becoming “the first president to understand and channel the spiritual and institutional power of the evangelical churches.” As president, Lincoln “assiduously courted” Protestant clergy, “cultivated” Christian journalists, corresponded frequently with religious reformers, and hosted Christian delegations at the White House. Probably not coincidentally, at the same time he knowingly invoked “religious language and themes” in characterizing the “fiery trial” that the nation was enduring. Zeitz concludes provocatively that, notwithstanding Lincoln’s rejection of the heart of evangelical faith, he deserves to be remembered as “the nation’s first evangelical president.”

So how should we remember this Republican-evangelical partnership that Lincoln did so much to nurture during the Civil War? Readers looking to justify Christian political activism will likely see it as cause for celebration. There’s no doubt that evangelical support was critical to Lincoln’s reelection in 1864. Considering that the Democratic platform that year opposed both emancipation and the continuation of the war, it’s plausible to argue that, humanly speaking, evangelical votes were crucial to the preservation of the union and the demise of slavery. Surely that vindicates evangelicals’ head-long plunge into electoral politics, doesn’t it?

Perhaps. Zeitz is unsure, and it’s the long-term consequences for American Christianity that give him pause. While southern Protestantism “retreated inward” after the Civil War and focused almost exclusively on individual salvation, in the North a “muscular brand of Protestantism” emerged that turned reflexively to the coercive power of government to advance its vision for a godly nation. This was a mindset learned during the war itself, Zeitz maintains, for it was during the war that a critical mass of northern clergy had “learned to view politics as the natural extension of their Christian ministry.”

The Almighty’s own purposes

When the French writer Alexis de Tocqueville visited the United States in the 1830s, the future author of Democracy in America was deeply impressed by the vitality of American Christianity, and he attributed it, more than any other factor, to the clergy’s determination to “mark their distance from, and avoid contact with, all parties.” They went so far, Tocqueville observed, as to teach “that in God’s eyes no one is damnable for his political views so long as those views are sincere.” That perspective had all but vanished a generation later. It is far too rare today.

In the interim, there has been more than enough evidence to suggest that, when Christians forge too close an alliance with any political leader, movement, or party, they run the risk of politicizing Christianity instead of Christianizing politics. We are tempted to compromise our convictions in order to cement the alliance; those who seek our votes are rewarded for helping us feel righteous as we do so.

If Abraham Lincoln was “the nation’s first evangelical president,” it is to his great credit that he stopped short of telling evangelical voters whatever they wanted to hear. When visitors to the White House were too dogmatic in revealing what God wanted him to do, he freely challenged them, sometimes testily. When reformers lobbied him during the war to support a constitutional amendment acknowledging the authority of “God Almighty” and “the Lord Jesus Christ,” Lincoln listened politely but never lent his support.

And when victory was practically assured, he preemptively undermined northern self-congratulation by insisting in his second inaugural address that God had answered the prayers of neither side fully. “The Almighty has his own purposes,” Lincoln observed—not a quote from the Bible, but a humbling truth that reverberates across its pages.

Robert Tracy McKenzie is professor of history and holds the Arthur Holmes Chair of Faith and Learning at Wheaton College. He is the author most recently of We the Fallen People: The Founders and the Future of American Democracy.

![[Video] More – Aghogho » GospelHotspot](https://gospelhotspot.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/More-Aghogho.jpeg)