In The Bible Tells Me So

In The Bible Tells Me So, I have a section called “Stories Work,” which is my conclusion to chapter 3, “God Likes Stories.”

My point there is that the writers of the biblical narratives were storytellers. They recalled the past “often the very distant past, not ‘objectively,’ but purposefully. They had skin in the game. These were their stories. They wove narratives of the past to give meaning to their present–to persuade, motivate, and inspire.” (pp. 75-76)

Stories work. Stories are powerful. Stories move us deeply, more so than statistics, news reports, or textbooks. We all know that. We only need to think about what holds our attention and makes us long for more—that book, film, or TV series that we wish wouldn’t end quite so soon, that story told of some deep, personal, transforming experience, whether painful or joyous.

The Bible, then, is a grand story. It meets us and then invites us to follow and join a world outside of our own, and lets us see ourselves and God differently in the process. Maybe that’s really the bottom line. The biblical story meets us where we are to disarm us and change how we look at ourselves—and God.

The Bible calls that change repentance. Maybe stories are where repentance can happen best. From what I can see, I think the Bible’s storytellers would agree. (129).

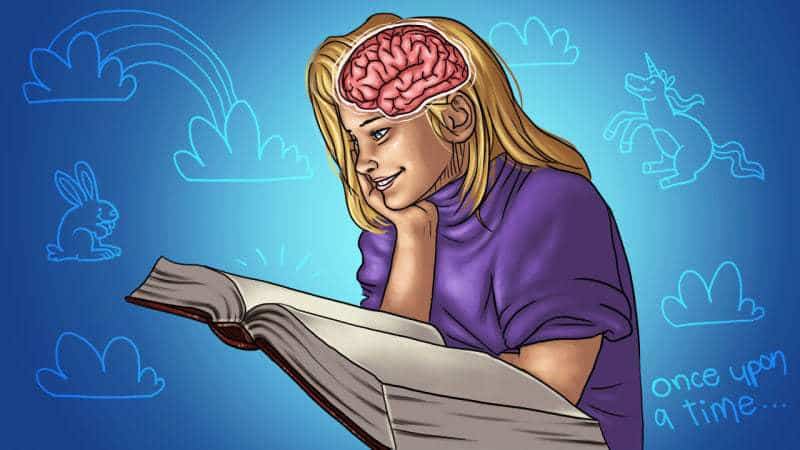

And then I stumbled upon this article, “The Science of Storytelling: Why Telling a Story is the Most Powerful Way to Activate Our Brains.” It was nice to see someone coming at this from a scientific angle.

Below is a snippet, but be sure to visit the site and read the whole article for yourself.

****

Our brain on stories: How our brains become more active when we tell stories

We all enjoy a good story, whether it’s a novel, a movie, or simply something one of our friends is explaining to us. But why do we feel so much more engaged when we hear a narrative about events?

It’s in fact quite simple. If we listen to a powerpoint presentation with boring bullet points, a certain part in the brain gets activated. Scientists call this Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area. Overall, it hits our language processing parts in the brain, where we decode words into meaning. And that’s it, nothing else happens.

When we are being told a story, things change dramatically. Not only are the language processing parts in our brain activated, but any other area in our brain that we would use when experiencing the events of the story are too.

If someone tells us about how delicious certain foods were, our sensory cortex lights up. If it’s about motion, our motor cortex gets active:

“Metaphors like ‘The singer had a velvet voice’ and ‘He had leathery hands’ roused the sensory cortex. […] Then, the brains of participants were scanned as they read sentences like ‘John grasped the object’ and ‘Pablo kicked the ball.’ The scans revealed activity in the motor cortex, which coordinates the body’s movements.”

A story can put your whole brain to work. And yet, it gets better:

When we tell stories to others that have really helped us shape our thinking and way of life, we can have the same effect on them too. The brains of the person telling a story and listening to it can synchronize, says Uri Hasson from Princeton:

“When the woman spoke English, the volunteers understood her story, and their brains synchronized. When she had activity in her insula, an emotional brain region, the listeners did too. When her frontal cortex lit up, so did theirs. By simply telling a story, the woman could plant ideas, thoughts and emotions into the listeners’ brains.”

Anything you’ve experienced, you can get others to experience the same. Or at least, get their brain areas that you’ve activated that way, active too . . . .

***The original version of this post appeared in December 2014. For my other books on biblical interpretation, see Inspiration and Incarnation (Baker 2005/2015) and The Sin of Certainty (HarperOne, 2016).***

![[Video] More – Aghogho » GospelHotspot](https://gospelhotspot.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/More-Aghogho.jpeg)