Note: This story includes mentions of graphic violence.

In the early years of the 20th century, Jacob August Riis was spotlighting the squalid New York City neighborhoods where hundreds of thousands were packed into dank and dangerous tenements. Half a world away, Alice Seeley Harris was working to expose the brutal regime terrorizing millions in the Congo Free State. In their quests to capture attention and inspire action, Riis and Harris each discovered a secret weapon: photographs.

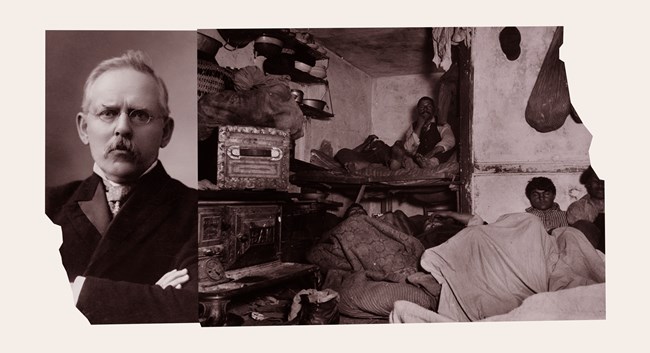

A reporter who immigrated to the US from Denmark when he was 21, Riis turned to new techniques of flash photography to illuminate the conditions of impoverished New Yorkers crammed into shoddy, windowless apartment buildings. Meanwhile, Harris and her husband John, both British Baptist missionaries in the Congo, smuggled out photos documenting the shocking atrocities being committed under the colonial rule of King Leopold II of Belgium.

Using the still-novel craft of photography, both Riis and Harris spurred national and international efforts that helped change the lives of millions of people. More than a century later, their efforts are honored in books, plays, and exhibitions and also remembered on World Photography Day—August 19—which pays tribute to the history of the craft and its power to influence people.

Neither Harris nor Riis would have described themselves as photographers. Riis was a writer and lecturer who implored the public to rise up and fight the misery he witnessed in the slums of New York City. He published articles describing how people lived like “vermin” and “inmates” in decrepit buildings that lacked ventilation and basic plumbing, but his message took on new power when he realized how flash photography could shed light on those issues. Riis took photos in sweatshops, alleys, underground bars, and filthy streets.

Image: Illustration by CT / Source Images: WikiMedia Commons

Left Photo: Jacob August Riis circa 1903. Right Photo: Lodgers in a crowded Bayard Street tenement taken in 1889.

When he presented these photos in lectures to groups in New York City and across the country, Riis would often end his talks with a slide of the cross or a picture of Jesus as he exhorted Christians, especially, to help the poor. According to Bonnie Yochelson and Daniel Czitrom, authors of Rediscovering Jacob Riis, “Riis was fundamentally a preacher who delivered powerful and entertaining sermons supported by statistics and photographs.”

In 1890 Riis published a book, How the Other Half Lives, with material from his lectures. The book, which includes photos that have since taken on iconic status, became a bestseller that remained in publication for decades.

Riis believed that Christians had a unique responsibility to engage in civic reform. In early 1903, he delivered a four-part lecture series to students at the Philadelphia Divinity School. A church without outreach programs, he said, was an “unfaithful steward.”

“Tell me, what sense is there in a man’s sitting comfortably in his pew of a Sunday, inviting his soul of the view of the beautiful mansion he has engaged on high, and letting his brother below wallow in his slough the while?” he wrote in The Peril and the Preservation of the Home.

Riis was convinced that strong outreach programs were essential to growing a church congregation, and he praised those with sewing and cooking schools, kindergartens, and soup kitchens. “That is the kind of faith that moves the world, mountains and all, and fills the churches! Not sermons, but service,” he wrote.

His photographs swayed audiences far more than his writings and lectures.

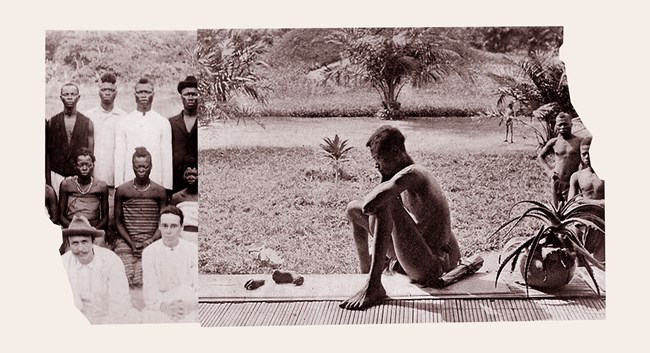

Alice Seeley Harris also lived out her faith in service. She was born in 1870 and raised by devout Christian parents in Wiltshire, England. She met John Harris through a mission outreach program in London, and they attended a missionary training college together before leaving for Africa four days after their 1898 wedding.

The Harrises planned to minister to isolated tribes in the Congo Free State, privately owned and run by King Leopold II of Belgium. He was enriching himself through the country’s rubber resources and using a private mercenary army, the Force Publique, to compel the Congolese to collect the sap of rubber vines for him. The Force Publique exploited the Congolese through rape, torture, widespread murder, and enslavement.

According to Dean Pavlaklis, history professor at Carroll College and author of British Humanitarianism and the Congo Reform Movement, “the brutality was so horrific that it may have wiped out half of the country’s population in just a few years.”

News of these atrocities hadn’t reached the outside world, so the Harrises were ignorant of the conditions before they arrived in Africa. Over time, however, villagers began telling them about the violence. Using the camera she had packed to take pictures of insects and wildlife, Alice began to document the abuse. She took hundreds of black and white photos that remain influential to this day.

One of Harris’s most famous images shows a father mourning over the severed hand and foot of his young daughter. The man, Nsala of Wala, had failed to gather his rubber quota, and sentries had killed and eaten his wife and daughter, giving him the severed limbs as tokens of his punishment.

Along with other missionaries and several leaders of humanitarian organizations, the Harrises participated in a letter-writing campaign to politicians and religious leaders around the world to stir up support against the abuse, and Alice’s photographs began showing up in publications. She and John toured Europe and America and used her photos to compel action.

The images made their way to Mark Twain, who in 1905 penned a scathing satirical pamphlet—King Leopold’s Soliloquy—that set off a firestorm and helped force Leopold to cede power in the region in 1908.

According to Joel Carpenter, director of the Nagel Institute for the Study of World Christianity at Calvin College, the Harrises—like other 19th-century missionaries who undertook similar campaigns—were rarely “systemic social reformers.”

They were “first and foremost people who loved other people. They [cared] about other people, saw that they’d been wronged, and [wanted] to make it right,” he told CT for the 2014 cover story, “The Surprising Discovery about Those Colonialist, Proselytizing Missionaries.”

Image: Illustration by CT / Source Images: WikiMedia Commons

Left Photo: The Reverend John Hoobis Harris (left front) and his wife Alice Seeley Harris (right front) with a group of indigenous people on their visit to the Belgian Congo. Right Photo: Nsala of Wala in Congo looks at the severed hand and foot of his five-year old daughter, 1904.

Their Christian advocacy work had much greater impact because of their photography.

Jacob Riis died in 1914 at age 65, after spending more than 30 years as a voice for social reform. A park and a settlement house in New York City bear his name. Alice was telling stories of injustice and abuse well into her 90s, before she died in 1970.

More than a century later, historians and others have taken renewed interest in the work of both Riis and Harris. An exhibition of Riis’s work toured the US and Denmark from 2015 to 2021, and several books have been written about him, including the aforementioned book by Yochelson and Czitrom.

Alice’s story was told in Don’t Call Me Lady: The Journey of Lady Alice Seeley Harris by Judy Pollard Smith, and some of her photographs were featured in What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843–1999, which won the prestigious Kraszna-Krausz Photography Book Award. Her story was also featured in a stage play, Possession, that premiered in East London in June 2023.

Riis and Harris believed God created them “for such a time as this” (Esther 4:14) and accepted their respective callings, despite the danger and personal cost to themselves and their families. Their photographs exposed the suffering of brothers and sisters in North America and Africa and, in so doing, established the camera as a tool for kingdom work.

Christina Ray Stanton is the award-winning author of Out of the Shadow of 9/11: An Inspiring Tale of Escape and Transformation.

![[Video] More – Aghogho » GospelHotspot](https://gospelhotspot.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/More-Aghogho.jpeg)