Dechurching is upon America, and everything from religious abuse to apathy to digital media have been named as culprits. This conversation has created many hypotheses, and as many implausible solutions. But most of the analyses of evangelical dechurching miss the deeper problem: an anemic church theology taught and modeled to churchgoers. The call to dechurching may, in fact, be coming from inside the building.

Daniel Williams wrote recently for CT that many evangelical luminaries were rarely consistent churchgoers themselves, and this was accompanied by a weak ecclesiology. Williams says the problem of dechurching today is not due simply to the poor precedent set by evangelical leaders. The problem is also the bedrock evangelical assumption that the Christian life is ultimately an individual adventure, fundamentally between God and the soul.

Within evangelical circles, whether intentionally or not, church has frequently been treated as an optional facet of the Christian life, primarily as a means to helping each of us live out a personal faith. Church is something that exists to assist one’s individual growth or spiritual experience. But this understanding misses the point, which is that church, as the body of Christ, is intrinsic to the life of faith.

Trying to address the crisis of dechurching by appealing to the practical benefits of the church to the individual is thus to try to revive the very problems which led us here to begin with. Appealing to individual experience is not the way forward. Sin is, from the beginning, a work of division and separation, a turning of a people into scattered individuals, and God’s cure cannot take the form of the disease.

As Gerhard Lohfink has put it, God will have a people, not just a collection of individuals. To be a people is to exist collectively through our prayer, our piety, and our purpose, inseparable from one another. When Scripture commands us to gather, it is because this is how God has called us and who God has called us to be: a new people among the peoples of the world, a holy temple into which individual stones have been joined together (Heb. 10:25; Eph. 2:21).

So, what are churches to do to regain their identity as a people? How do we, in the words of Williams, redeem an evangelical ecclesiology?

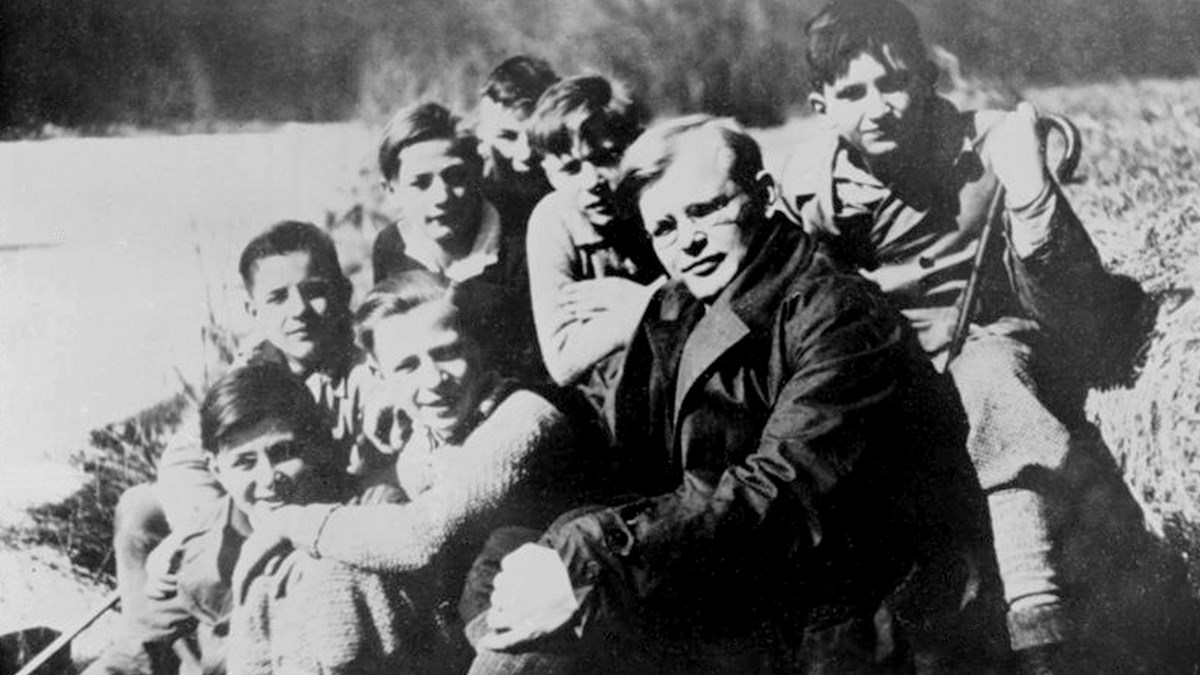

Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Life Together was written in another time of church crisis, when Bonhoeffer was helping to establish a new seminary for the fledgling Confessing Church. The Confessing Church had been established as an alternative to the German National Church, which had altered its confession to include a new clause offering allegiance to the Fuhrer.

In linking itself fully to Adolf Hitler, the National Church attempted to establish itself as a true “church of the people”—certainly a strategy for long-term survival, but at a heretical cost. Though Bonhoeffer’s context is different, challenges to the church’s cultural survival today force us to ask the same question: What is “the church” that we are trying to save?

The church, Bonhoeffer writes, is centered not on individual experience or on the ability of a strong leader to cast a compelling vision. These may sustain churches, but only for a time. Instead, the church in all its practices is meant to be a community—a people who encounters Christ through and with one another, and not merely a group of individuals who live alongside one another.

This community is to be centered on Christ, who is present in its midst. Christ has called each person beyond themselves to be a part of this corporate body. It is Christ alone by which the church survives and succeeds, and Christ alone who calls forth a body centered on being God’s people in the world.

If we come to Bonhoeffer hoping that, by making our churches into communities, they will become successful, we miss his point: that community is what makes it a church at all.

For Bonhoeffer, an individual Christian life is impossible. Because the Spirit has drawn together a body, we encounter Christ through the words we speak to one another, through the Communion we eat together, and through the Scriptures we read and live out alongside each other. The practices which he commends in Life Together are not so much about making the church successful as they are about making the church a community.

But the work of becoming a people does not mean adopting a new program. It means turning our attention once again to the familiar practices of the Christian life—congregational singing, the reading of Scripture, eating together—only with a profounder end in mind: to become a community. In this way, although Life Together is thoroughly practical, it is also deeply theological.

When we read Scripture together, for example, he advises selecting longer passages that remind us of God’s ongoing work among his people, a work which the church of today is grafted into. Such passages focus on the centuries-old story we share with Christians throughout history, as opposed to focusing on a person’s individual context. In particular, he commends the Psalms, the prayerbook of Israel, which direct our attention to the church’s ongoing connection with Israel and to our calling to be a people.

Likewise, when we sing corporately, he commends singing in unison to center our attention not on our individual experiences, but on the reality that God has made us into one people. And when we pray together, Bonhoeffer asks us to pray for those things that concern our common life first, not for those things which belong solely to the individual.

When we scatter throughout the week, there is ample time for Christ to speak to our individual concerns and our personal lives through the Scriptures. But even these times, Bonhoeffer says, are for the edification of the larger body, that we might bring back to the church those things which Christ has given us while we were apart from one another.

A similar ethos applies to how we read Scripture, share meals, and think about missions. If the aim of church practice is that we might be drawn together as a people, then not only does what we do matter, but how we do it.

As Bonhoeffer reminds us, “Christian brotherhood is not an idea which we must realize; it is rather a reality created by God in Christ in which we may participate.” Practices of prayer, singing, and service are not magic pills, but invitations of God into a deeper reality that Christ has made possible.

We invite all the believers among us—not just the excellent readers—to be readers of Scripture. We eat in such a way and in such a time that all can gather. We do missions not to enable people to become religiously affiliated individuals, but to become members of a community where gifts will be called out and where we might receive the words of Christ from others.

In commenting on the reciprocal nature of prayer, Bonhoeffer says what makes it possible for an individual to pray for the group is “the intercession of all the others for him and for his prayer.” He asks, “How could one person pray the prayer of the fellowship without being steadied and upheld in prayer by the fellowship itself?”

Whatever spiritual life the individual has depends first on the community that God in Christ is creating. The church here is not an afterthought: It is the presumption. God is creating a people whose life together in Christ makes possible all our individual journeys into the world.

The Spirit draws us from all places and goes with us into all the world—whether we are gathered or not. But this going out is for the sake of being brought back in. We are meant to be a people whose lives are knit together, not a people who simply make do on our own.

If dechurching is to be addressed, the response cannot be more of the same that led us here. For the church offers us something that cannot be categorized in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: The church gives us Jesus and makes us part of Christ’s body. And it is in this body that we become Christian, in which we experience the presence of Christ and are changed.

Just as the disciples learned together to hear the voice of Jesus, so also do we. We must not merely revise our faulty evangelical ecclesiology, seeing the church as an additional aid to the life of faith-needs. Instead, we must abandon such thinking altogether. And if this faulty vision of church is what dechurching leaves behind, then all the better.

Myles Werntz is the author of From Isolation to Community: A Renewed Vision of Christian Life Together. He writes at Christian Ethics in the Wild and teaches at Abilene Christian University.

![[Video] More – Aghogho » GospelHotspot](https://gospelhotspot.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/More-Aghogho.jpeg)